When Should You Grant a Stock Warrant to a Lender?

February 7, 2023

Founders and execs at SaaS companies hold much (or most) of their net worth in the equity of their companies. They’re obviously very reluctant to sell or issue more stock, options, or warrants (warrants are essentially “options for non-employees”). After all, each such issuance dilutes the current owners, even if only by 1%.

Yet, there is a longstanding practice of granting options (to employees) and warrants (to lenders). So there must be some rationale — why would a thoughtful, strong negotiator willingly agree to dilution of his or her stock by issuing a lender’s warrant?

There are two main reasons it can be to your advantage to grant a small but meaningful equity warrant to a lender. The first is pricing, and the second is strategy. (There are also some pitfalls to look out for.)

Simple Math: Time-Shifting the Cost

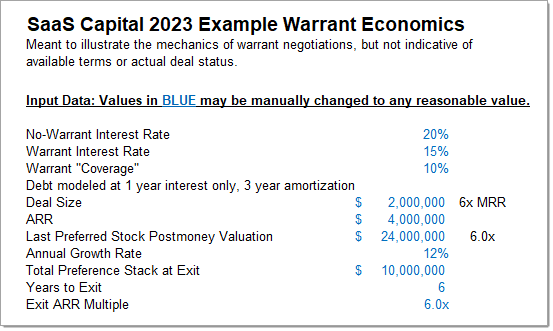

The first reason is simple math: by granting some future upside, you can negotiate a lower current cash flow burden. Say the “true” cost of debt is 20%. If the lender believes a warrant will eventually add at least 5% worth of return, you could offer a warrant in exchange for reducing the interest rate to 15%.

In this way, it’s somewhat like “points” on a mortgage; a housing lender is generally willing to trade off more points for a lower rate, or vice-versa. (The big difference here is that “points” have a known value up front in a mortgage, while a warrant is for an unknown future value.)

It’s also similar to how you might negotiate a cash vs. options package for an important new hire. By offering a piece of uncertain future upside with options, you might be able to economize on the near-term cash burden of paying salary.

It’s also similar to how you might negotiate a cash vs. options package for an important new hire. By offering a piece of uncertain future upside with options, you might be able to economize on the near-term cash burden of paying salary.

In effect, by offering a warrant to a lender, you’re time-shifting a part of your cost of debt out into the future. For a growing SaaS business, it’s a reasonable assumption that the company will have more ability to pay that cost in the future than it does today.

We’ve prepared a brief example showing how different sets of assumptions about the future can result in a warrant deal either being cheaper overall or more expensive overall. You can download it here. Either way, a warrant deal should work out to have a lower near-term cash flow burden.

Nuanced Strategy: Alignment of Interests

The second reason is more nuanced, and it’s strategic or behavioral rather than strictly math. You should want your lender to always be “rooting for” the founders/owners to succeed, and a sure-fire way to encourage that is to give the lender a little bit of the same incentive (equity) the owners have.

A lender will always be motivated first to avoid losses and reliably to earn interest. That’s OK. In normal times, and when everything is ticking along nicely, this lines up 100% with rooting for the owners — after all, if the business is growing and producing cash flow, then it can both pay its obligations to lenders and grow its owners’ equity value.

But the life of a private SaaS company is not always perfectly smooth and normal. There might come at any time a situation that requires discretion and flexibility from your capital providers (including equity investors and/or lenders). Ensuring alignment via shared incentives can make things vastly easier and more likely to result in a win-win. The goal isn’t to make the lender care more about equity than debt; it’s to make sure they don’t care only about the debt.

Our partners have worked hundreds of private tech company financings, and along the way, have seen many, many circumstances that are like the cautionary tale below. (Names and dates have been changed, but the numbers and behaviors are true.)

A Cautionary Tale

Company C closed a debt deal two years ago but was wary of dilution. The company chose Lender L because they didn’t require a warrant; instead, they charged a higher interest rate. Things started out well enough, but during the second year, a slowdown in their customers’ target vertical brought growth to a halt. As a result, cash got tight right around the time the loan started to amortize (payments jumped 3x, from interest-only to principal-plus-interest). Company C was now down to a few months’ cash.

Company C had also just gotten an acquisition offer from a larger company — but at a lowball valuation. The founders were confident that if they could get through this tight spot, and get growth back on track, they would be able to hold out for a much better offer (or get to profitability and have no pressure to sell out prematurely). So, they talked to Lender L: would they be willing to extend the amortization, to ease cash flows for another 6-12 months of runway?

Unbeknownst to Company C, at the same time, Lender L’s credit committee was tightening its view toward risk. Lender L refused any concession to Company C, instead demanding full on-time payment of the amortization. The lender had a very cold logic: Company C could always sell out to the big company, for a price that would more than cover the loan (even if that left little for the founders).

Because Lender L had no warrant, they had no financial incentive to support anything but the lowest-risk path for themselves, which was to effectively force the company into liquidating at a lowball price.

To be clear: Lender L will pay a reputational price for this behavior, and Company C’s founders will probably tell this horror story to every other founder they meet for a decade. But this all might have been avoided if Lender L’s incentive was more aligned with the owners.

Having Lender L hold some of their return in a warrant instead of current-pay interest would have forced L to think more holistically and long-term, instead of focusing with tunnel-vision on the short-term debt payback.

Pitfalls and Red Flags

That said — and acknowledging that we are biased as lenders ourselves — in all fairness there are a few things to watch out for as abusive or inappropriate use of warrants.

Smaller or non-strategic vendors or lenders probably shouldn’t be granted warrants for things like equipment leasing or an office rental. In normal times, you’ll have lots of options, or even multiple vendors for those needs, such as different leases on different items (whereas, you will only have one senior lender typically).

Another pitfall is abusive deals with compounding equity features. We’ve seen lenders wind up with 30% equity ownership, after a perfect storm of compounding equity features plus a period of low performance or tight fundraising conditions. You should be able to figure out — and cap — the maximum equity the lender gets in a deal.

Normally, senior lender or venture debt warrants, however calculated, come out to low-single-digit dilution. (We say “however calculated” because there are lots of ways to do the math, but at the end of the day what you should focus on is the percentage of the total equity.) If there’s ever a scenario where your lender could wind up over 10% ownership of the company, we’d assert that it’s actually an equity deal and should be evaluated as such.

Finally, we’d advise caution any time a warrant is to have a valuation based on a growth or revenue metric to be applied in the future. “Kicking the can” like this sometimes helps solve a gridlock, but it’s important to keep the mechanics simple, objective, and comprehensible. Years later, perhaps with different people involved, figuring out what was meant and what is fair can create headaches. We generally prefer a simpler approach using a flat, fixed valuation.

Conclusion

In summary, negotiating a senior debt deal that includes a warrant can sometimes result in a lower interest rate and a better-aligned relationship with an important capital partner. The warrant shouldn’t be an automatic feature of every financing, but should never be completely off the table, either, because it has a rational purpose for both parties.

Our Approach

Who Is SaaS Capital?

SaaS Capital® is the leading provider of long-term Credit Facilities to SaaS companies.

Read MoreSubscribe